Violence Footprint Report

Team: Mariëlle van Es, Fran Lambrick, Vedtey Ngoun, Esme Staunton Howe

Sussex Sustainable Research Programme Principal Investigator: Paul Gilbert

1. Introduction

Over recent decades there has been a dramatic increase in land grabbing and extractive development in Cambodia [1]. These investments in natural resource exploitation have had a major influence on rural livelihoods in Cambodia. Through various mechanisms, such as the granting of economic land concessions to foreign companies and infrastructure projects among others people have lost access to their lands [2]. The impacts of these land grabs among others include forced displacement, child labour, environmental damage and an increase of poverty and food insecurity [3]. These land grabs are driven by multiple forces such as the movement of global capital; opportunities for capital accumulation and increased control over land for the political elite; and blurring boundaries between state and corporate actors [4].

State actors and violence by these state actors plays a major role in these land grabs [5]. Resistance to megaprojects such as large plantation and construction projects is linked to an increased criminalization of social protest and violations of the human rights of activists, and land defenders. Many who actively resist development projects that negatively impact them suffer from multiple forms of violence such as threats, criminalisation, physical attacks, killings, ‘slow violence’ due to the loss of lands and livelihoods, and lack of protection [6]. In Cambodia, this is also compounded by the shrinking space for civil society that has contributed to an increase in confrontational clashes between security forces and land rights activists in recent years. In 2018, Amnesty International ranked Cambodia as one of the deadliest countries for female activists [7]. The Cambodian government has deployed a narrative casting environmental defenders as a threat to social stability, and has accused environmental and land defenders of inciting revolution [8].

Land rights defenders and corporate abuses in Cambodia

These human rights violations are often linked to the activities of foreign companies and investors, either because of their link to local companies or due to direct operations in Cambodia. Investors and domestic elites compete for land and its resources with local inhabitants.

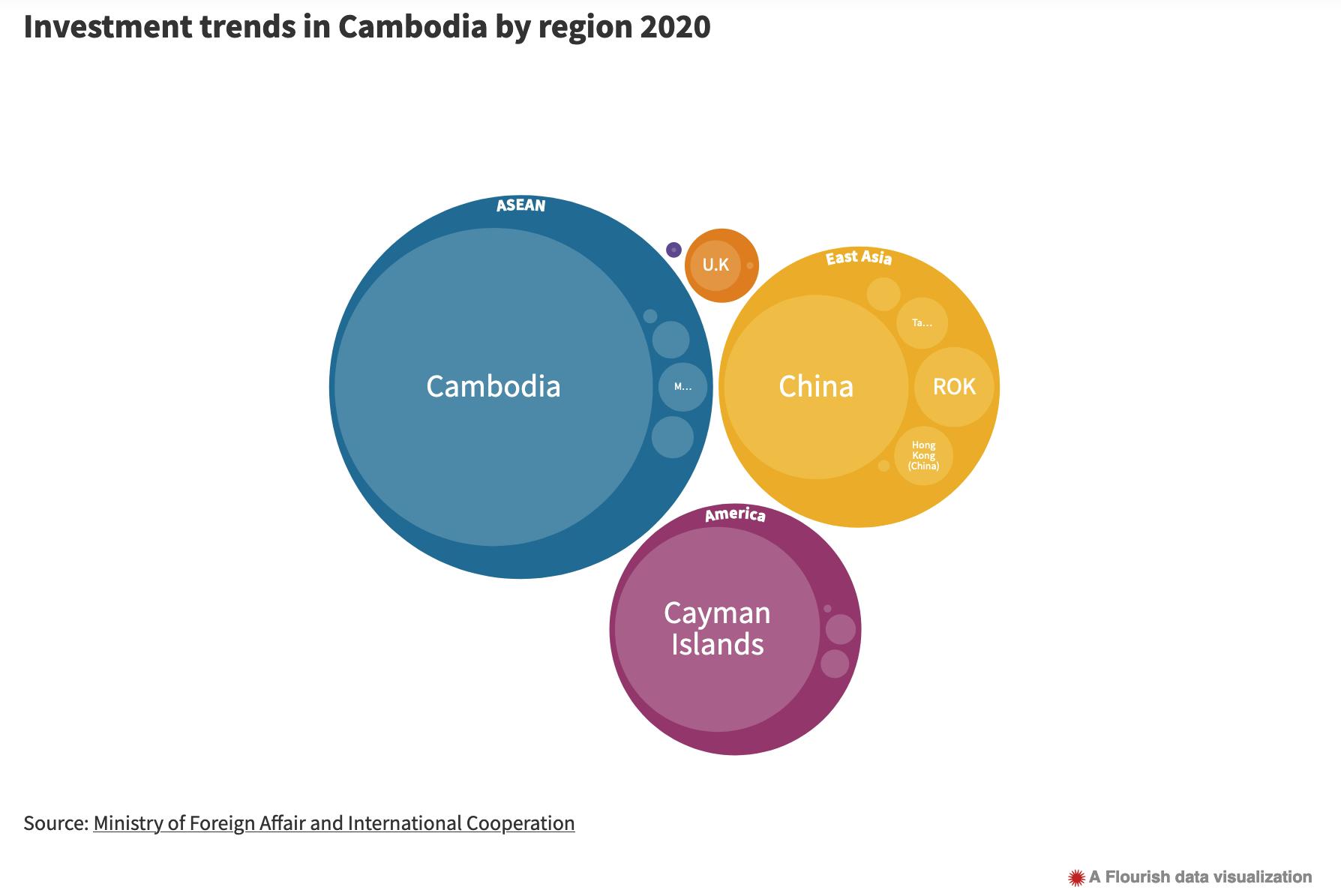

Recently the Americas has emerged as a top investor in Cambodia, overtaking East Asian countries. In 2018, China was the top foreign investor in Cambodia, accounting for 3,179 million USD, followed by Japan (882 million USD). However, Chinese investment has declined since then, and in 2020 China was overtaken by the Cayman Islands with 1,722 million USD in capital investment. That year the Cayman Islands also topped the world’s Financial Secrecy Index, published by the Tax Justice Network [9]. Among European countries, the UK invested the greatest amount in Cambodia (105 million USD).

Datasheet 1 provides an overview of more than 55 cases linked to corporate abuses in Cambodia. The table shows a wide range of cases, including the construction of hydropower dams, rubber and sugar plantations, the construction of large infrastructure projects and others. All of these cases are linked to violence against environmental defenders. Some of these cases are linked to foreign investment, or to companies registered in OECD countries. In this research we investigated the ties between companies and human rights violations in three case studies, and the possibilities to hold those companies and investors accountable.

Violence Footprint project

The Violence Footprint project examines the responsibility of foreign registered companies and investors for human rights abuses in Cambodia. We particularly focus on three different case studies with a link to the UK. This research is supported by the Sussex Sustainability Research Partnership (SSRP) and is a collaboration of the Department of Global Studies from Sussex University with Not1More. The aim of the project is to document violence against environment and land defenders in Cambodia linked to foreign investment, creating an online database and data visualisation of financial and corporate relationships in three case studies.. The violence footprint research aims to make data accessible and to assist environmental defenders in holding UK companies accountable, and to encourage authorities and financial institutions to incorporate due diligence projects [10].

Methodology

For this project field work in Cambodia was executed by Not1More, working in collaboration with a Cambodian NGO in November 2022 – January 2023, with desk based research into the drivers and actors involved in human rights abuses in three cases in Cambodia. People from three different case study areas were interviewed about their resistance to corporate abuses. A semi-structured interview method was used. Newspaper articles, documentation of NGOs and academic literature were used to investigate the relation between UK-companies and their link to human rights abuses in Cambodia. This was complemented with a literature review on social land concessions, accountability mechanisms in the UK and accountability mechanisms of the World Bank and OECD. In this research we used Orbis, a database with information about private companies, to investigate the link between shareholders and the companies related to human rights violations in Cambodia.

2. Data Sheet 1 Violence Footprint Data

The datasheet shows an overview of violent incidents against environmental defenders. The incidents related to EU or US companies are highlighted in yellow. However, this overview is not an exhaustive record of incidents.

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1CpNuOwMsEmKOCrafbtxVBSDsVqsAaEMK0exP7bZI3_Y/edit#gid=2116083381

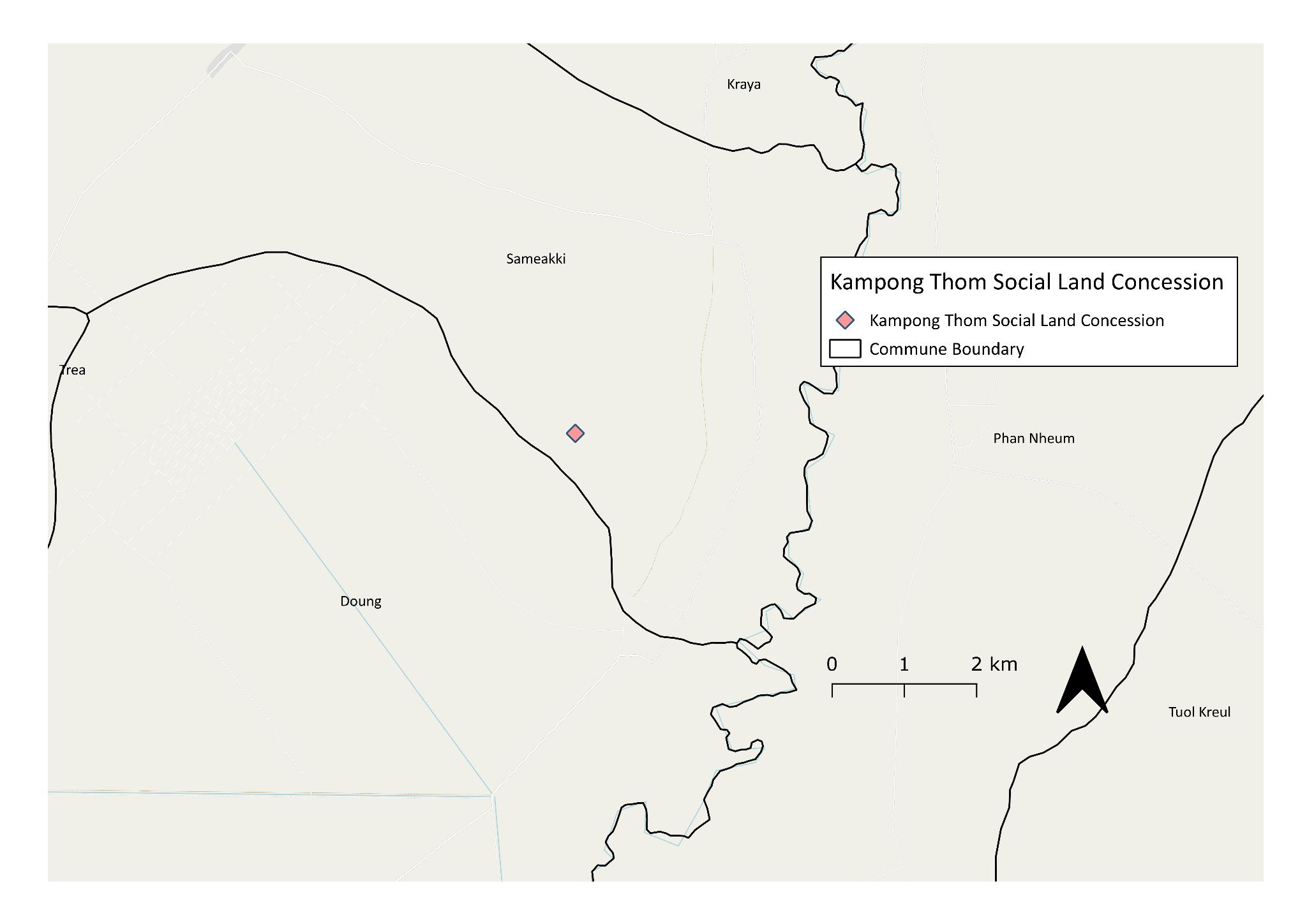

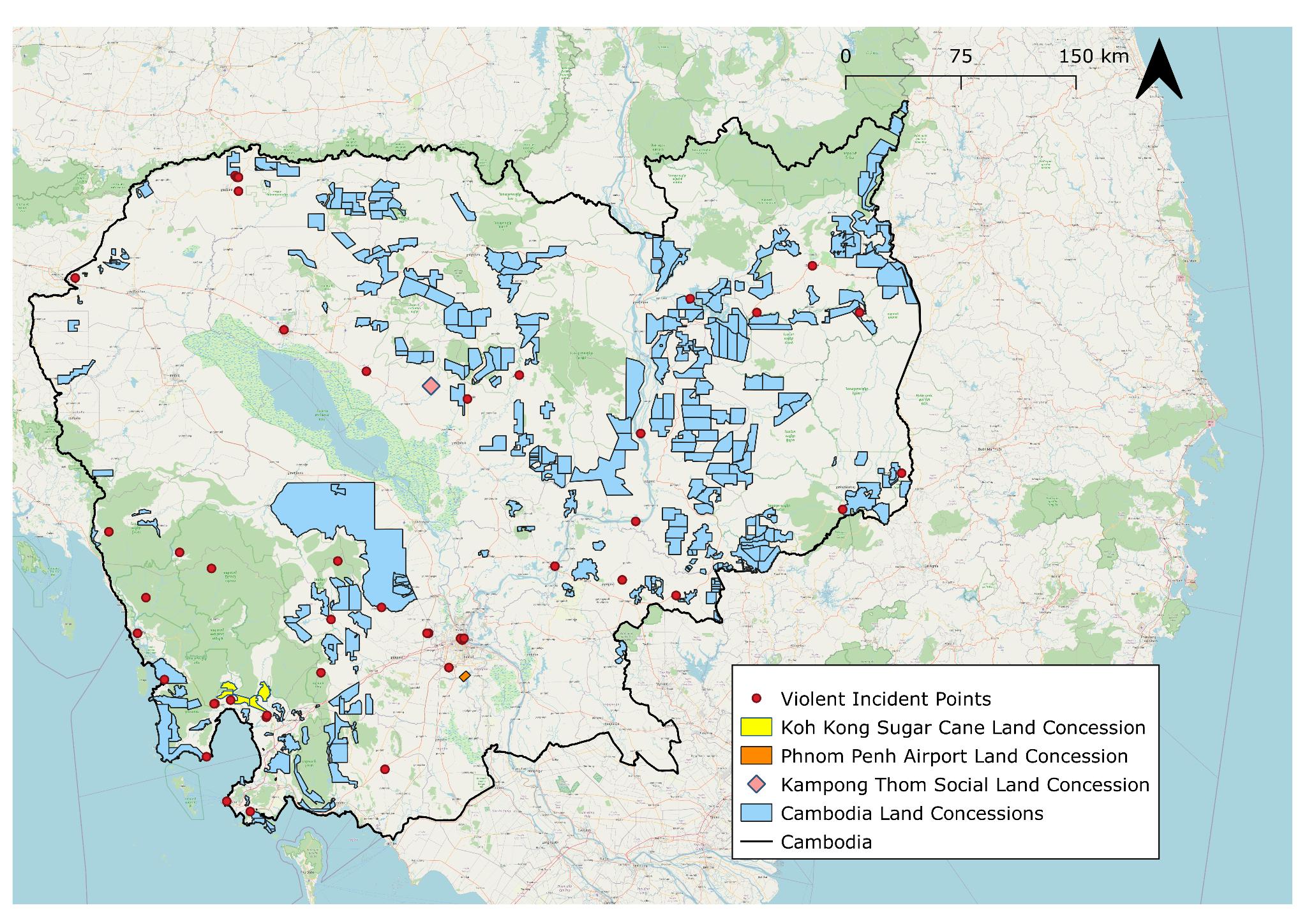

3. Map 1 Overview of Violence Footprint Data

4. Case studies

Introduction

The three case profiles below aim to show the involvement of companies and banks from the Global North in human rights violations in Cambodia. Two case profiles concentrate on the role of UK Stock Exchange listed companies in land grabbing in Cambodia – linked to sugar production in Cambodia’s south west, and the new airport development concession. The third case profile shows how a World Bank project has led to new disputes around land, and fails to improve the tenure security of the rural poor.

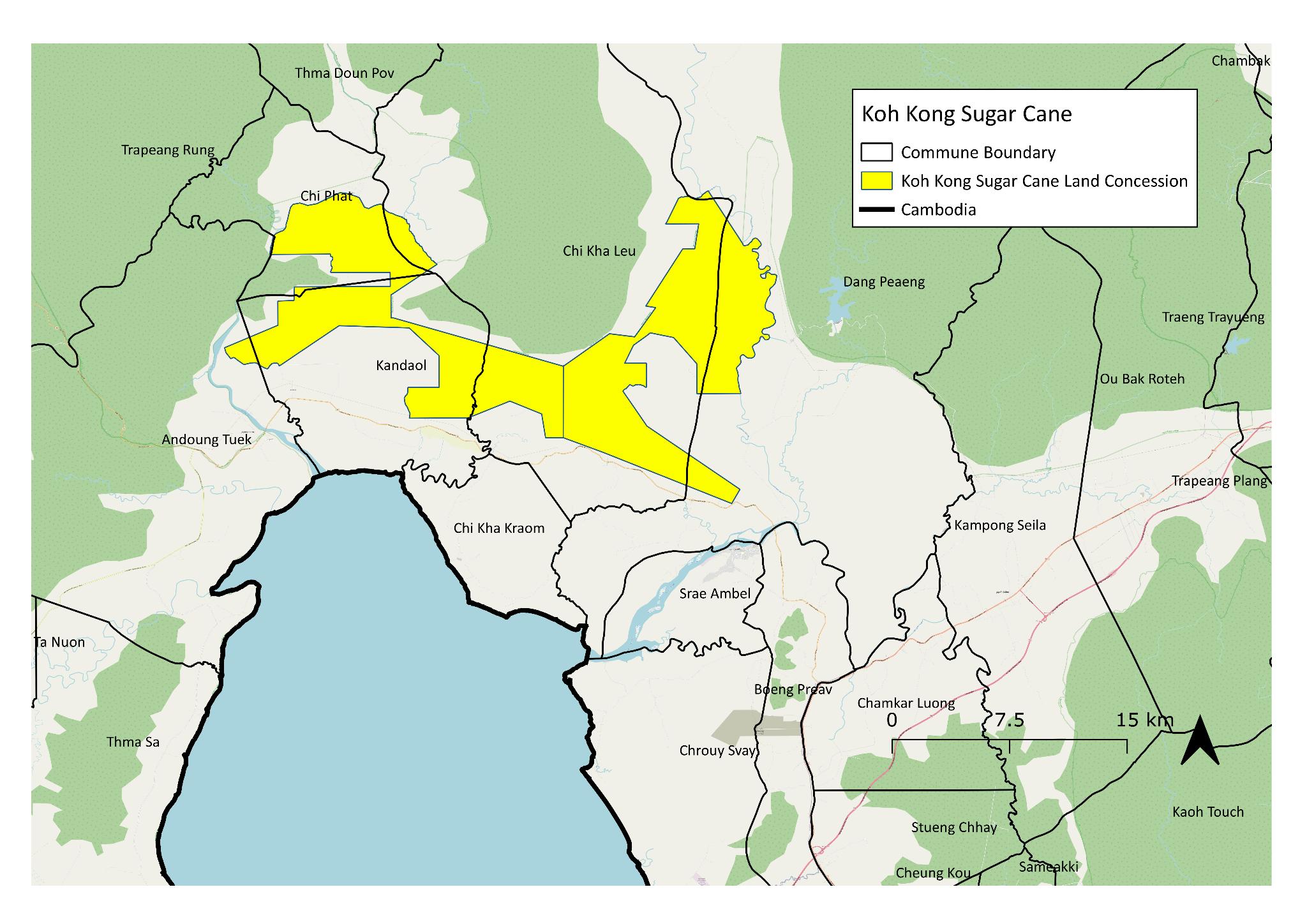

4.1. Case profile Koh Kong Sugar Cane

Over the past decades investments in sugar cane plantations in Cambodia have increased due to the everything but arms program of the European Union, which allows for duty and quota free access to the European market for products from low income countries [11]. However, much of the land that is used for these plantations is grabbed from small scale farmers. This is also the case in Koh Kong province. More than 450 families in Koh Kong province have been evicted from their lands for agro-industrial sugar cane plantations. In total 5 groups of more than 1,500 families in Tham Bang, Sre Ambil and Botum Sakor district are advocating for fair compensation and justice. Some of these groups have been advocating for more than a decade, whereas other groups are recently formed [12].

Overview of community actions and impact

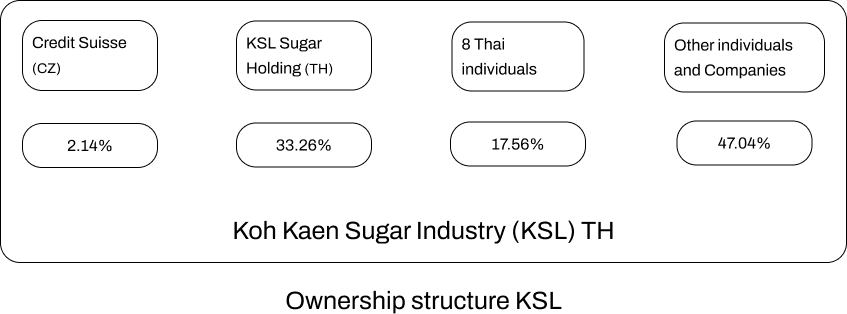

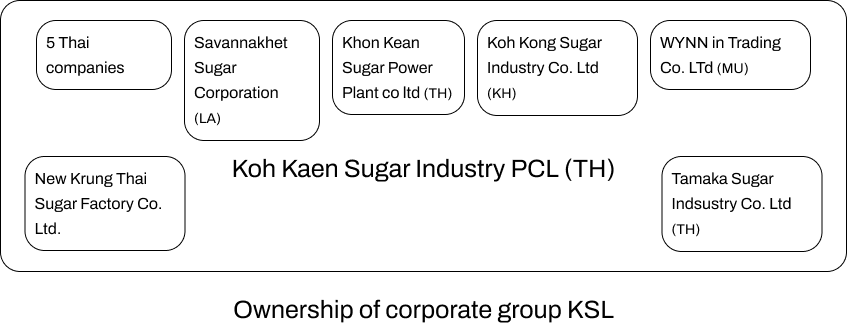

In 2006 the Cambodian government granted Economic Land Concessions (ELC) for 20,000 ha in total to two Cambodian companies: Koh Kong Plantation Co Ltd and Koh Kong Sugar Industry Co. Ltd. These Cambodian companies are owned by the Thai firm KSL group, a Taiwanese company and a Cambodian senator [13].

The process of land acquisition has not followed the Cambodian law. The land was owned by the villagers and not the state and only state land can be part of the ELC program. Besides this, the total area of land exceeds the 10,000 hectares, the maximum for an ELC. The communities were never consulted about the plantation and received no compensation. More than 450 families were evicted by the military police on behalf of the government of Cambodia in 2006 [14].

In 2006, a group of 200 families started to protest against the land clearance agents. Authorities fired upwards and one woman was injured during this protest. In total at least seven villages had significant injuries and two villagers have been shot and wounded. The homes and possessions of the villagers on the land have been destroyed. In total the group lost 1365.07 hectares of land.

In 2008 the land clearing started. The crops and orchards of the communities were damaged and cattle was killed. Since then these families have been struggling to maintain their livelihoods because they are no longer able to harvest their crops. This means that they can no longer afford to send their kids to school and the children need to work to contribute to the family income. Some families have migrated to cities to find a job in for example construction [15].

The KSL group has been accused of land grabbing, child labour and forced evictions. During harvest time from December to February children work on the Cambodian plantations of KSL. The work is heavy and poorly paid. Workers receive about $2.5 for 100 bunches of sugarcane per day. However, picking 100 bunches is often impossible, especially for woman an children since the work is heavy [16].

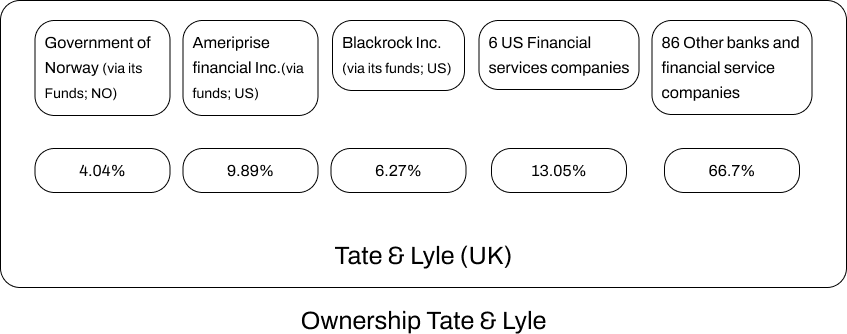

The British sugar firm Tate & Lyle, the largest European sugar cane producer, has imported sugar cane from these lands since 2010 [17]. Tate & Lyle got its supplies from Cambodia through the KSL Group. Tate & Lyle sells its sugar to large food and beverage companies in the EU, such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. In 2010 Tate & Lyle was sold to the American Sugar Holdings (ASR group), the largest sugar refiner in the world [18].

The community filed a complaint at the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand in 2010. They demanded an investigation of the NHRC of Thailand to ensure justice. In 2015 the NHRC recognized the human rights violations at KSL plantations [19]. Besides this, they filed a complaint at Bonsucro, an organisation that monitors sugar companies and provides a platform for sustainable sugarcane production. In 2013 Tate & Lyle was suspended from the organization because of the human rights violations in Koh Kong province [20]. Because Tate & Lyle is owned by ASR, a US company, the community also filed a complaint at the US National Contact Point for the OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises about the human rights violations on sugarcane plantations in Koh Kong province. These are voluntary code of conduct for multinational companies [21].The NCP tries to mediate in conflicts. This complaint was supported by the NGOs Community Legal Education Center (CLEC) and EarthRights international. In 2013 the voluntary mediation process ended because the different parties could not reach an agreement [22].

In 2013, a group of 200 villagers filed a case against Tate & Lyle in the high court in London. The filing of the case was supported by CLEC. The community claims that they were evicted from their lands and demand fair compensation of the value of the sugar grown on the land that still belongs to them [23]. In 2017 Tate & Lyle offered compensation of $3000 and 1.5 ha to the group of 200 villagers. Other groups did not receive any compensation [24].

Compensation

The company claims that affected communities have been compensated. In total 580 families were compensated. This involved 1618.45 hectares of land and $285,000. The compensation process was led by a government agency. However, many families are still demanding fair compensation for the loss of the land. In 2014, 24 families received $2,000 from the state. This created friction and division within the community of 200 villagers. After the filing of the case, Tate&Lyle offered the 200 group $3,000 and 1,5 hectares of land in 2017. Nevertheless, the families did not receive the compensation yet. The transfer of the money is organized by Oxfam. However, the 1,886 hectares of land that were available for compensation are taken away from the Southern Cardamom Mountain National Park and the Biodiversity Corridor system for Natural Resources Protection. In 2017, the Group 317 community received 2 hectares of land and $ 3,000 [25]. In 2021, Tate&Lyle refused to pay any more compensation [26].

The group of 200 families requested a social land concession (SLC) for 600 families since the land provided by the compensation program is not enough to feed their families. The SLC program is a program of the Cambodian government to redistribute state owned land to landless and near landless people and aims to improve the food security of people who lost land under the ELC program. The request for the SLC is still being processed [27].

In June 2023 9 people were arrested because of their advocacy work against Tate & Lyle [28].

Support

The communities are supported by Equitable Cambodia through legal trainings, advocacy campaigns and assisting the communities in writing complaints to international organizations to seek proper and fair compensation. In 2012 Equitable Cambodia launched the Clean Sugar campaign in which they aimed to raise awareness about the human rights abuses that occur on land granted for agro-industrial sugarcane plantations [29]. They called for a boycott Cambodian ‘blood sugar’ and demanded the European Union to investigate the human rights violations around the sugarcane production in Cambodia [30].

Timeline Koh Kong sugarcane trial

2006

Cambodian government granted economic land concessions for 20,000 ha to two sugar companies owned by KSL. More than 450 families were evicted from their land by the military police on behalf of the Government of Cambodia.

2007

Local activist involved in the case was killed.

2007

Villagers filed civil and criminal complaints at the Koh Kong Provincial Court.

2008

Start of land clearing, orchards and crops of the community were damaged and cattle were killed.

2009

ASR buys Tate & Lyle’s sugar operations.

2010

Tate & Lyle received its first sugar from the plantation.

2010

A publication about the abuses in Koh Kong was send to Tate & Lyle.

2010

Villagers file a complaint at the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT).

2011

A complaint at Bonsucro, a global organization for sustainable sugarcane production was filed.

2012

Complaint at U.S. National Contact Point (NCP) was filed.

2012

The Cambodian court referred the case to the Koh Kong Provincial Cadastral Survey.

2013

NCP issued a final statement and the dispute was not resolved.

2013

200 families filed a case at the UK High Court against Tate & Lyle demanding fair compensation for the sugar cultivated on their land. The villagers are represented by Jones Day.

2013

Tate & Lyle was suspended from Bonsucro initiative.

2014

Community refused offer from Tate & Lyle.

2014

Leigh Day takes over the case, case is delayed.

2015

National Human Rights Commission of Thailand recognized the human rights violations at the KSL plantations.

2016

Villagers offer a petition to local authorities and demand to solve the dispute.

2017

Group of 200 receives compensation.

2019

The Department of Land Management denied a community request to intervene in the case. The villagers demand implementation of the agreement between Tate & Lyle, KSL and the community.

2021

Tate & Lyle refused to pay compensation.

Map Tate & Lyle case

Company data Tate & Lyle

The following company data shows the ownership structure of Tate & Lyle and the KSL group. It also shows information about the companies that are related to KSL. These maps show possible pressure points for advocacy (e.g. OECD countries, etc.).

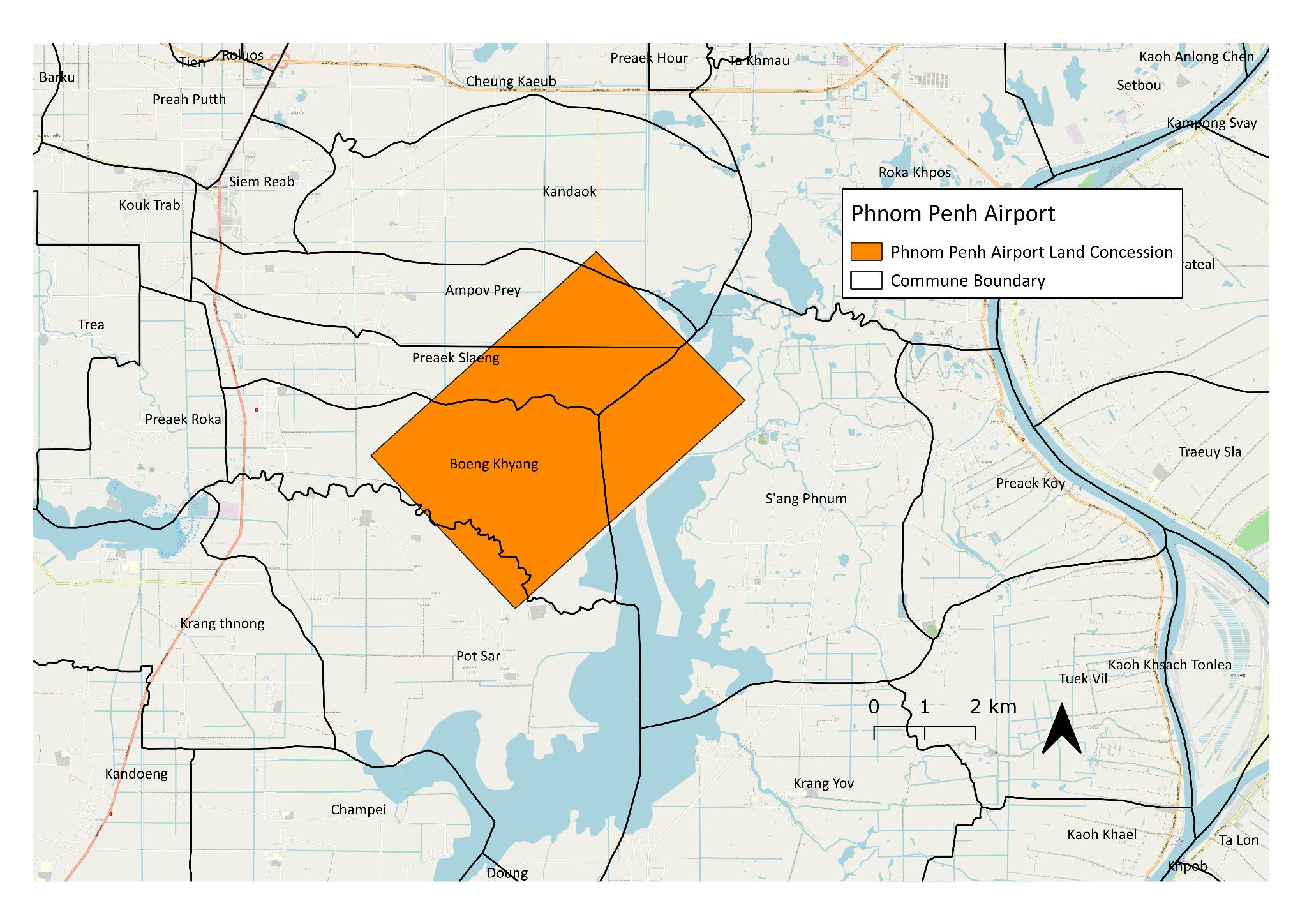

4.2. Case profile New Phnom Penh airport case

Introduction

The development of the new Phnom Penh airport is leading to a violent dispute over land in Kandal and Takeo province, Cambodia. After the governments announced the plans for the new airport in January 2018, the price of land in Kandal increased rapidly, creating opportunities for land speculation and land grabbing in the area. About 330 families are advocating for fair compensation of their lands. These families use the land for farming and obtained titles to the land in the past. Their lands cover an area of 163 hectares [31].

The new airport is built to be able to keep up with the increasing growth of tourism in Cambodia. In 2019, over 6.6 million tourists visited Cambodia [32]. The tourism sector counted for 16.3% of the GNP in 2017 [33]. It is claimed that the airport will boost Cambodia’s economic growth and will be a hub for tourists in the region. The project is built in three phases and phase one is currently being constructed. It is expected that the new airport will open in 2025. The project also involves the construction of a new highway to Phnom Penh. The project covers an area of 2,600 hectares, which are mainly rice fields and lakes now [34].

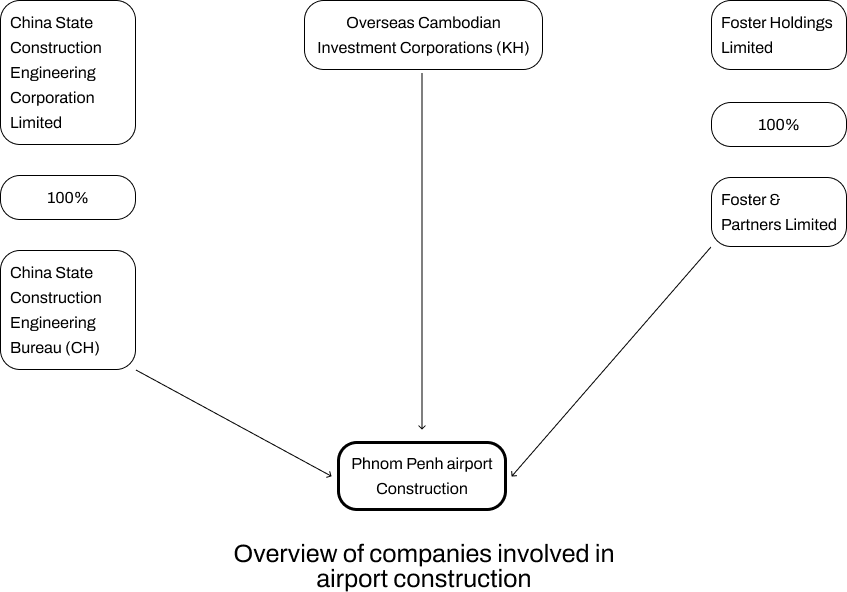

The project is led by the Cambodia Airport Investment Company (CAIC), which is a joint venture between the Cambodian state represented by the secretariat of civil aviation, owning 10%, and the Overseas Cambodian Investment Corporation (OCIC), the largest investment company in country, which owns 90% of the stocks [35]. The company is owned by the well-connected Oknha Pung Kheav Se. CAIC was established in 2018. The project costs $1.5 billion in total from which $1.1 billion is borrowed from the China Development Bank. The airport is designed by Foster & Partners, a UK company. The airport is build by a Chinese constructor, the China Construction Third Engineering Bureau. Construction started in 2022 [36].

Compensation

In 2017 and 2018 land prices in the area rapidly increased. Prices rose from $10-$14 per square meter to $40 to $100 per square meter. From late 2018 onwards land brokers were buying land in the area for $70 to $100 per square meter [37]. During this time the project was seen as an opportunity for economic development. Several families did not sell the land because they depend on the land for their livelihoods. In September 2019 the government issued a letter stating that the compensation price from the company is $8 per square meter or relocation and ordered landowners to stop selling land at the location of the airport. This letter was the start of the land dispute. Besides the ongoing land dispute, the relocation will create new disputes around land in the future since the land for relocation has not been bought yet. About 330 families say the land is worth between $60-70 per square meter and do not accept the price set by the government but demand compensation with the market price [38]. With the current offer the communities are not able to buy the same size of land they lost and will lose their livelihoods, which will force them into homelessness and poverty. However, about 16 families accepted the offer from the company. The company claims that most villagers accepted the offer and only a few are demanding more money. Since 2019 the affected families have demanded national, district and provincial authorities to intervene in the dispute. Nevertheless, the government authorities did not respond to the villagers’ demands [39].

In 2021 the conflict escalated and violence increased. In May 2021, 48 people living in Boeung Khyang camped out at their rice fields and blocked the road to prevent the clearing of their farmland for the construction of the airport. They demand fair compensation for their land and crops. The villagers say that the company violated their agreement with them. In the agreement it is stated that there will be no clearing of land without negotiating fair compensation with the owner. In response to these protests the authorities destroyed a road to the communities farmland and houses [40].

On September 12, 2021, 100 people tried to stop the construction company’s machinery from clearing the land since the land dispute is not solved yet. About 400 police officers barricaded the area, leading to a clash between the community and the police. The police dispersed the protest with tear gas and violence. The police arrested 30 people. Nine of these people are facing a case at the provincial court. They are accused of intentional violence and obstruction to public officials with aggravating circumstances and incitement to commit a felony [41]. They were sent to detention and released on bail on September 21. The police claimed that 13 police officers were seriously injured. The other protestors were forced to sign a contract to not protest again and were pressured to accept the company’s offer. In November 2022, the 9 were acquitted by the provincial court. After these protests some families accepted the low price. The authorities are pressuring people to sell their land by cutting off electricity, dismantling homes in the area and take away tractors and motorbikes. The land dispute also creates friction within the community since some people accepted the low price and others did not. Both the company and the government authorities are inviting people for private talks [42].

In response to these violent protests, 31 civil society organisations issued a joint statement demanding fair compensation for the families who will be evicted from their lands for the construction of the airport. In this statement they demand the company to follow international and national human rights laws and raise their concerns about the escalation of the land conflict [43].

In December 2021, 200 people filed a complaint to the National Assembly because the land dispute was not yet resolved. The land of several farmers had already been cleared by the company. However, the farmers have not received compensation yet [44].

In February 2022 the affected community sent a petition to the Ministry of Justice and the National Assembly. In this month, OCIC started to excavate rice fields and wetlands that are owned by the villagers of Kampong Talong. Police and military officials were dispatched to prevent any protest against these works. The authorities also threatened to arrest the villagers [45].

In April 2022 the construction of the new road started without notice. Nevertheless, the land dispute remains unsolved and the land still belongs to the villagers. Crops and houses were damaged by the construction of the new road [46].

On the 3th of October 2022, 84 civil society organisations, including ADHOC, LICADHO and Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR) issued a statement to push the government to solve the land disputes around the new Phnom Penh airport. The government did not respond to this request. More families accepted the price set by the company. The construction of the airport continues while the land dispute is not settled [47].

Timeline New Phnom Penh airport case

2017

Issuing of official notification for the establishment of CAIC.

2018

CAIC is established, a joint venture between the government and OCIC.

2018

Protest at district hall against company that grabbed land from the community [38].

2019

Kandal Provincial Authorities issue official letter with compensation offer.

2021

48 people block the road and camped out at their rice fields.

2021

100 people block the road, 30 got arrested, 9 face criminal charges.

2021

Joint statement of civil society organisations to demand solving of land dispute.

2021

Communities protest at commune hall and demand compensation for communal land used for the airport development project.

2021

Complaint to National Assembly was filed.

2022

The community sends a petition letter to the Ministry of Justice and the National Assembly.

2022

OCIC starts clearing of rice fields.

2022

Start of construction of new road.

2022

Prime minister issues letter to Kandal governor to solve the land dispute.

2022

Community meets with representatives from company and Ministry of Land Management to discuss compensation [39].

2022

84 civil society organisations issue a statement to push government to solve the land dispute.

2022

9 protestors are acquitted by the provincial court.

Map Airport case

Overview Companies Airport case

The following figure provides an overview of all companies involved in the construction of the airport.

4.4. Datasheet 2 corporate links and ownership

The table below provides an overview of the shareholders of the KSL group and Tate & Lyle. For the KSL group the shareholders who are located in an OECD country are shown in green. The red flag companies and individuals have been reported on personal investment and sanction lists. This overview of shareholders provides information on possible entry points for advocacy and shows which companies are related to human rights violations in Cambodia. This table was created with help of Orbis, a database on company data.

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1_ialz886PF08bXgJ0W3tMxI4gBD2ZyYWdBlEb13ivqU/edit#gid=0

5. Accountability mechanisms

There are several mechanisms to hold companies accountable for human rights violations. However, these are voluntary guidelines and therefore, the outcomes are non-binding. Worldwide various groups are advocating for legislation to hold companies accountable for human rights abuses and environmental harm. The annex provides an overview of the information that is needed to file a complaint at each of the accountability mechanisms below.

OECD guidelines

This is a set of guidelines and principles for multinational companies for responsible business conduct. The OECD guidelines apply to multinational enterprises headquartered in an OECD member or adherent state or to a multinational enterprise operatinging inside an OECD member or adherent state. These guidelines are a set of non-binding principles and standards. These guidelines include guidelines on protection of human rights and due diligence. For example, a company should prevent or mitigate adverse impacts, engage with relevant stakeholders and apply the principles of responsible business conduct. The harms should be related to one of the chapters of the OECD guidelines.65 The OECD guidelines can be applied to raise public awareness about an issue, attract the attention of the government to an issue, acknowledgement by a company or remedy and compensations for the harms [66].

These guidelines are supported by a complaint mechanism through the National Contact Points (NCP). These NCPs are responsible for the implementation of the guidelines and can have a mediating role in conflicts. The outcomes of this procedure are not legally enforceable and the NCPs usually lack the capacity to enforce their decisions. Besides this, only a very limited number of cases result in improved conditions for victims of corporate abuses. Also, since NCPs refuse to do additional investigations, the community bears the burden of providing evidence [67]. The process of preparing the complaint takes several months and the process itself takes about one year but can last several years. Also the complaint process requires a lot of resources such as labor costs, travel costs and consultancy costs [68].

World Bank guidelines

The World Bank has several internal accountability mechanisms, such as the Inspection Panel and the grievance redress service.

Inspection Panel

The inspection panel was the first internal accountability mechanism of the World Bank. The panel consists of three members that are appointed by the Board of Executive directors for five years. The accountability mechanism consists of an inspection panel that reviews the compliance and the dispute resolution service, which was established to facilitate voluntary dispute resolution between the complainants and the borrowing government. The inspection panel allows people from the Global South to directly hold the World Bank accountable for the social and environmental costs of World Bank projects. The mechanism covers projects funded by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Development Association and trust funds managed by the World Bank [69].

Two or more people who are harmed by a World Bank project can submit a request for inspection directly or through a representative. When people who are harmed by the project file a complaint the Bank reviews if the Bank has followed its internal policies and procedures to safeguard people and the environment and investigates if the non-compliance of these policies and procedures causes harm to the affected community. Examples of cases are forced relocation for infrastructural projects, environmental degradation as result of World Bank projects or lack of participation in planning and implementation of the projects [70]. However, the World Bank accountability mechanism does not address corruption, fraud or issues related to procurement of the project [71].

When the complaint is considered to be eligible, the community and the borrower are given the option for dispute resolution. The maximum length of the dispute resolution process is one year. When parties reach agreement the case is closed. When no agreement is reached the case is closed and the panel reports its findings to the board of the World Bank[72]. The board of executive directors has to make a final decision on the panel’s findings. However, the board resists these investigations and often rejects the claim that the environmental and social policies of the bank have been violated. Because of this the scope of the inspection panel is limited [73].

Grievance Redress Service

In 2015 the Grievance Redress Service (GRS) was established and allows communities and individuals to directly submit complaints to the World Bank if they feel that a project is having a negative impact on their community or the environment. This complaint is reviewed and a solution is proposed. This accountability mechanism operates parallel to the inspection panel [74]. The GRS is part of the World Bank management. It aims to resolve issues when project-level grievance mechanisms are absent or not sufficient [75].

Due diligence laws UK

The UK currently does not have legislation to hold companies accountable for human rights abuses and environmental harm. There are voluntary guidelines which were developed after the adoption of the UN Guiding Principles on business and human rights. Civil society groups, businesses and investors are campaigning for a law on human rights due diligence and corporate liability.

Another option to hold UK companies accountable for human or environmental abuses elsewhere is by taking legal action in the UK court. Taking legal action is possible when a UK company is connected to a company in another country through contracts with this company or ownership [76]. The goal of these cases is usually to receive financial compensation. In most cases the company and the community reach an agreement for compensation before the case is taken into court. However, when the case is settled the company does not have to admit its human rights and environmental abuses. Besides this, companies are not required to change their way of operating. Also, going to court is a long and expensive process and can take 2-5 years [77]. There has been an increase in court cases and these cases have shown that companies have a responsibility for the activities of their subsidiaries and their impact on communities and the environment [78].

6. Conclusion

The Violence Footprint project shows the links between UK registered companies and human rights violations in Cambodia. It shows several opportunities for advocacy by mapping the UK registered companies or financiers of these companies. It demonstrates that although UK registered companies do not directly operate in Cambodia in all cases, they use services or products linked to human rights violations. It highlights that corporate accountability is complex and that communities have limited possibilities to hold multinational enterprises or the World Bank accountable for environmental or social harm. These accountability processes take a lot of time and (financial) resources. Besides this, to successfully implement these mechanisms participation of the company and state is required. A major concern is that most of these mechanisms are based on voluntary principles. Also, most of these accountability mechanisms such as the OECD guidelines only apply to countries in the Global North. Whereas countries from the Global South like China are also important actors in issues around corporate accountability and land grabbing. However, there are very few possibilities to hold these companies accountable. Also, there are hardly any transparency principles reinforced in Cambodia which hinders the opportunity to identify openings for advocacy for company shareholders and subsidiaries. More information and research on how to hold these companies accountable is needed. This should be combined with more regulation for due diligence and free, prior and informed consent processes.

7. References

British Institute of international and comparative law (2020) A UK failure to prevent mechansims for corporate human rights harms. Available online (06-03-2023).

https://www.biicl.org/publications/a-uk-failure-to-prevent-mechanism-for-corporate-human-rights-harms

Business and human rights resource centre (2021) UK civil society campaign for a law on corporate human rights abuses. Available online (06-03-2023).

https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/uk-civil-society-campaign-for-a-new-law-on-corporate-human-rights-abuses

Business and human rights resource centre (no date) Koh Kong sugar plantation lawsuits (re Cambodia) Available online (07-03-2023).

https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/koh-kong-sugar-plantation-lawsuits-re-cambodia

Cambodian Center for human rights (no date) Case profile: Land communities impacted by the development of the new Phnom Penh international airport (Techno Krong Takhmao International Airport) by Overseas Cambodia Investment Corporation.

Camps, F., (2022) Phnom Penh New Airport Terminal 40 percent complete. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://cambodianess.com/article/phnom-penh-new-airport-terminal-60-percent-complete

Channyday, C., (2018) Villagers in land dispute with airport developers meet with district authorities. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/villagers-land-dispute-airport-developers-meet-district-authorities

Chakrya, S., (2021) Villagers protest farmland clearing for Phnom Penh airport project. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/villagers-protest-farmland-clearing-phnom-penh-airport-project

Core (2016) Holding UK companies to account in the English courts for harming people in other countries. Available online (06-03-2023).

https://corporatejusticecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/CORE-Basic-Guide_English_final_2016.pdf

Core (2020) Debating mandatory human rights due diligence legislation: a reality check. Available online (06-03-2023).

https://corporatejusticecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/debating-mhrdd-legislation-a-reality-check.pdf

Dara, V., (2019) Government to spend $4 million on Lased II. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/government-spend-4-million-lased-ii

Dara, V., (2021) Nine face charges in Kandal land dispute. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/nine-face-charges-kandal-land-dispute

Earthrights International (2012) Cambodians file complaint with US government against Domino Sugar Parent. Available online (07-03-2023).

http://equitablecambodia.org/website/data/Our-Case/Sugar_Case/ERI%20vs%20ASR%20OECD%20Complaint%20Press%20Release.pdf

Equitable Cambodia (2013) Final statement for US National Contact Point for the OECD Guidelines for multinational enterprises. Available online (07-03-2023).

Equitable Cambodia (no date) The Sugar Case. Available online (07-03-2023).

http://equitablecambodia.org/website/article/3-2015.html

FIDH (no date) Corporate Accountability for human rights abuses: a guide for victims and NGOs on resource mechanisms. Available online (06-03-2023).

https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/corporate_accountability_guide_version_web.pdf

Flynn, G. (2021) The great Koh Kong land rush: areas stripped of protection by Cambodian gov’t being bought up. Available online (7-12-2022).

https://news.mongabay.com/2021/10/the-great-koh-kong-land-rush-areas-stripped-of-protection-by-cambodian-govt-being-bought-up

Government of the United Kingdom (2013) Good Business: implementing the UN guiding principles on business and human rights. Available online (06-03-2023).

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/236901/BHR_Action_Plan_-_final_online_version_1_.pdf

Government of the United Kingdom (2019). UK government modern slavery statement progress report (accessible version). Available online (06-03-2023).

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-government-modern-slavery-statement-progress-report/uk-government-modern-slavery-statement-progress-report-accessible-version

Government of the United Kingdom (2020) Policy Paper: UK National Action Plan on implementing the UN guiding principles on business and human rights: progress update, May, 2020 Available online (06-03-2023).

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/implementing-the-un-guiding-principles-on-business-and-human-rights-may-2020-update/uk-national-action-plan-on-implementing-the-un-guiding-principles-on-business-and-human-rights-progress-update-may-2020

Hak, S., Underhill-Sem, Y., & Ngin, C. (2022). Indigenous peoples’ responses to land exclusions: emotions, affective links and power relations. Third World Quarterly, 43(3), 525-542.

Hennings, A. (2019). The dark underbelly of land struggles: The instrumentalization of female activism and emotional resistance in Cambodia. Critical Asian Studies, 51(1), 103-119.

Hodal, K. (2013) Tate & Lyle sugar supplier accused over child labour Available online (10-01-2023).

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jul/09/tate-lyle-sugar-child-labour-accusation

International Development Association (n.d.) What is IDA? Available online (7-12-2022).

https://ida.worldbank.org/en/what-is-ida

IOL (2012) Cambodians call for ‘blood sugar’ boycott. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://www.iol.co.za/news/world/cambodians-call-for-blood-sugar-boycott-1334389

Lamb, V., Schoenberger, L., Middleton, C., & Un, B. (2017). Gendered eviction, protest and recovery: a feminist political ecology engagement with land grabbing in rural Cambodia. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(6), 1215-1234.

LICADHO (2015) On stony ground: A look into social land concessions. Available online (7-12-2022).

https://www.licadho-cambodia.org/reports/files/208LICADHOReport-LASEDSocialLandConcessions2015-English.pdf

McCorquodale, R., & Nolan, J. (2021). The effectiveness of human rights due diligence for preventing business human rights abuses. Netherlands International Law Review, 1-24.

Minea, S., (2021) Airport land dispute complaint taken by 200 to National Assembly. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50991226/airport-land-dispute-complaint-taken-by-200-to-national-assembly

Narim, K., (2022) Villagers’ land cleared for mega-airport project despite ongoing disputes. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://cambojanews.com/villagers-lands-cleared-for-mega-airport-project-despite-ongoing-disputes

National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (2015) Findings Report. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://earthrights.org/wp-content/uploads/unofficial_english_translation_-_tnhrc_report_on_findings_-_koh_kong_land_concession_cambodia_0.pdf

Neef, A., Touch, S., & Chiengthong, J. (2013). The politics and ethics of land concessions in rural Cambodia. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 26(6), 1085-1103.

Ngin, C., & Neef, A. (2021). Contested Land Restitution Processes in Cambodia. Land, 10(5), 482.

OCIC (no date) About.

https://www.ocic.com.kh/about

OECD (2018) Sturcutral Policy country notes. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://www.oecd.org/dev/asia-pacific/saeo-2019-Cambodia.pdf

OECD Watch (no date) OECD & NCP. Available online (07-07-2023).

https://www.oecdwatch.org/oecd-ncps

Office of the Hing Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (no date) The UN guiding principles on business and human rights an introduction. Available online (06-03-2023).

https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Business/Intro_Guiding_PrinciplesBusinessHR.pdf

OpenDevelopment Cambodia (2015) Social land concessions. Available online (07-02-2022).

https://opendevelopmentcambodia.net/topics/social-land-concessions/#:~:text=Social%20Land%20Concessions%20(SLCs)%20are,or%20generate%20income%20through%20agriculture

Oxfam International (2013) Sugar and land in Sre Ambel, Koh Kong, Cambodia. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/302505/cs-sugar-land-cambodia-021013-en.pdf;jsessionid=3F025A0987F0446EBCDC4E4523AD7229?sequence=4

Rasch, E. D. (2017). Citizens, criminalization and violence in natural resource conflicts in Latin America. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, (103), 131-142.

Ratcliffe, R. (2021) Tate & Lyle accused of betraying Cambodia families whose land was allegedly taken. Available online (10-01-2023).

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/jan/02/tate-lyle-accused-of-betraying-cambodia-families-whose-land-was-allegedly-taken

RFA (2020) Cambodia’s land concessions yield few benefits, sow social and environmental devastation. Available online (07-12-2022).

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/cambodia/concessions-08262020174829.html

Sarath, S., (2022) Families affected by Kandal airport demand clarity on compensation. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://cambojanews.com/families-affected-by-kandal-airport-demand-clarity-on-compensation

Sarath, S., (2022) New airport developer begins clearing farmland, though compensation hasn’t been finalized. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://cambojanews.com/new-airport-developer-begins-clearing-farmland-though-compensation-hasnt-been-finalized

Savi, K., (2019) Armed police stand by amid Kampong Thom protest. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/armed-police-stand-amid-kampong-thom-protest

Schoenberger, L., & Beban, A. (2018). “They turn us into criminals”: Embodiments of fear in Cambodian land grabbing. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(5), 1338-1353.

Sokun, K., (2019) Villagers accuse UK firm of failing to pay compensation in sugar dispute. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://vodenglish.news/villagers-accuse-uk-firm-of-failing-to-pay-compensation-in-sugar-dispute

Song Mao & others (2013) In the High Court of Justice Queen’s Bench Devision Commercial Court. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/files/media/documents/tate-lyle-particular-of-claim-28-mar-2013.pdf

Sopheavotey, L., & Vantha, P., (2021) Civil Society Groups call for proper compensation in Kandal land dispute. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://cambodianess.com/article/civil-society-groups-call-for-proper-compensation-in-kandal-land-dispute

Soriththeavy, K. (2022) World Bank land giveaway marred by problems. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://vodenglish.news/world-bank-land-giveaway-marred-with-problems

Sotheary,P., (2016) Koh Kong villagers deliver petitions. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/koh-kong-villagers-deliver-petitions

Tate & Lyle Sugars (no date) ASR Group. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://www.tateandlylesugars.com/about-us/asr

Teehan, S., (2013) Sugar Industry monito drops UK’s Tate & Lyle amid Koh Kong charges. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/sugar-industry-monitor-drops-uks-tate-lyle-amid-koh-kong-charges

University of Sussex (no date) Mapping the ‘violence footprint’ of UK-listed companies and their operations in Cambodia. Available online (07-03-2023).

https://www.sussex.ac.uk/research/centres/sussex-sustainability-research-programme/research/mapping-violence-footprint

World Bank (2020 A) Cambodia $93 million project of improve land tenure security for poor farmers, indigenous communities. Available online (7-12-2022).

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/26/cambodia-93-million-project-to-improve-land-tenure-security-for-poor-farmers-indigenous-communities

World Bank (2020B) International Development Association Project Appraisal Document. Available online (7-12-2022).

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/499101593482869813/pdf/Cambodia-Third-Land-Allocation-for-Social-and-Economic-Development-Project.pdf

World Bank (no date) International tourism, number of arrivals Cambodia. Available online (08-03-2023).

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?locations=KH

8. Annex

8.1. OECD guidelines

In what situations can this be used?

The Guidelines Grievance mechanism is designed to resolve disputes between companies and individuals or groups that are negatively impacted by the companies business activities. The OECD guidelines apply to any company headquartered in an OECD country or adherent state, wherever they operate in the world.

Who is this for?

Any individual or organisation with an interest in the case can submit a case to a NCP.

What is the process?

A case is submitted to a NCP in a country where the company is operating or where its headquarters are located. The process consists of an initial assessment, dialogues and conclusion.

You will need the following information:

The complaint should be filed in English or the official language in which the NCP is located. Some NCPs have specific requirements on which information should be included. Therefore, check the website of the NCP before filing a complaint. The application should include the following information:

1) Who is being harmed by the enterprise’s violations and who is causing, directly or indirectly the harms to the environment or people.

2) Where and when did the harm occur or are they expected to occur.

3) Which activities of the company violated the OECD guidelines?

4) ‘How have the company’s actions harmed communities, workers or the environment?

5) Why are the complainants seeking the help of the NCP?

Time Frame

The initial assessment takes about 3 months. When the case is further examined the NCP facilitates a dialogue, conciliation and/or mediation. This phase takes about 6 months. The conclusion phase in which a report is made and a final statement is issued takes 3 months. However, there are many cases in which the process took longer.

Further information:

https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/ncps/how-do-ncps-handle-cases.htm

https://www.oecdwatch.org/how-to-file-a-complaint

8.2. World Bank

Inspection Panel

In what situation can this be used?

The Inspection Panel is the World Bank’s complaints mechanism. The Inspection Panel evaluates the process followed by the World Bank and can be used when a World Bank project harms or is expected to harm two or more local people. The project should be funded by the IDA or IBRD.

Who is this for?

Two or more local people or their representatives that are negatively affected by a World Bank project.

What is the process?

The process consists of an investigation phase and an eligibility phase.

The complaint can be submitted in local language or English.

The complaint can be submitted via email or mail to Executive Secretary World Bank Inspection Panel Mail Stop: MC10-1007 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 United States of America

F: + 1 202 522 0916

E: ipanel@worldbank.org

T: (for questions only) + 1 202 458 5200

You will need the following information:

1) Clearly define the specific violations of the WB policies and procedures and which harms these violations cause

2) Record of steps that have been taken to resolve the problem with the WB management

3) When possible: evidence for the harm or expected harm

Further information:

https://www.inspectionpanel.org/how-to-file-complaint

https://www.somo.nl/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/The-World-Bank-Inspection-Panel.pdf

Grievance Redress Mechanism

In what situation can this be used?

The GRS can be used when individuals or communities are harmed or expected to be harmed by a World Bank project. The project should be under preparation, active or closed for less than 15 months.

Who is this for?

Individuals or communities or their representatives who are harmed by or expected to be harmed by a World Bank project.

What is the process?

The GRS will review the issue and propose a solution. Complaints can be send through the online form on the website of the World Bank, by email or mail to the World Banks headquarters in Washington DC, USA or a country office:

https://wbgcmsgrs.powerappsportals.com/en-US/new-complaint

Email: grievances@worldbank.org

You will need the following information:

1) The project subject of the compliant

2) The projects adverse impacts

3) Identify the individuals submitting the complaint

4) When available: supporting evidence of the harms caused by the project or the expected harms

Further information:

8.3. Court case

In what situation can this be used?

Legal action can be used when individuals or communities have been harmed by company activities or activities of its subsidiary.

Who is this for?

For individuals or communities affected by human rights violations by a UK company or its subsidiaries.

What is the process?

The case will go to a court process and this results in a trial. Most cases reach settlement before trial. A legal procedure requires many resources.

You will need the following information:

1) Evidence about the company’s involvement in the harm

2) A letter of Claim

Timeframe

Depends on how complicated the issue is, how many people are involved or if settlement is reached before trial. If no settlement is reached it takes 2-5 years.